When viewing images of the American secret police murdering a woman in broad daylight, I am reminded of a quote from the Battle of Helms Deep that expresses my frustration and helplessness. While under attack, Theodan, king of Rohan mutters “what can man do against such reckless hate.” I have thought about this line often as every day as I am bombarded with more horrors wrought by my own government.

My invocation of “Lord of the Rings” may come as a surprise because conservative thought leaders have interpreted Tolkien’s “Lord of The Rings” as a direct allegory to support their ideology. Writers like Curtis Yarvin consistently emphasize the ugliest and most racist pieces of Tolkien, and claim his tale of kindness, brotherhood, and basic decency as their own. As if Tolkien would feel affinity for the collection of tyrants, meddlers, and thieves that control our current government. No, Tolkien’s story was not meant to be straightjacketed into some white supremacists vision of “the west,” but instead is a story about sorrow, memory, and beauty told on the timescale of one life and generations. A story my mind returns to again and again in these evil times.

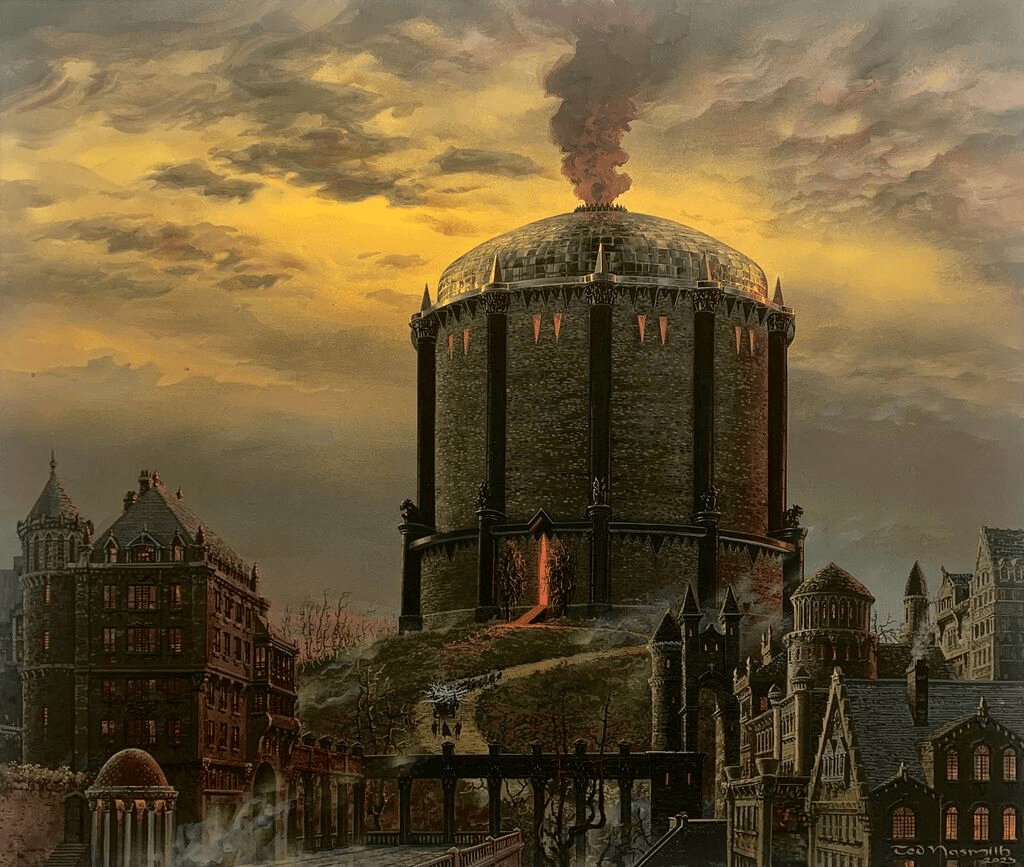

I have long believed that the secret to why Tolkien’s adult fairy tale continues to enchant young and old alike is that he has a remarkable knack for names. This comes as no surprise given his background as a linguist (he did write Quenya before the first lines of Bilbo’s tale), but it is no less remarkable how a simple name can evoke such feelings of peace, dread, or sorrow. Eldar names like Caras Galadohn, or Gil-Galad, Edain names like Minas Tirith, or Numenor, and sites of ancient evils like Angmar, or Barad-Dur conjure entire histories even though a place called Rohan never existed. The history and meaning behind these names add poignancy to key moments within the story, such as when Frodo makes the decision to take the ring to Mordor and Elrond states that his name will be remembered among the great heroes of the first age like Turin Turambar and Earendil. Even if the reader has no knowledge of who these made up people are, it still stirs something within, a feeling that the quest to destroy the ring is not isolated, but fits into a history, a legacy of heroes.

What I find most laced through Tolkien’s names, especially those of ancient Eldar or Edain places and people, is an undercurrent of sorrow. A wistful memory of some older time where great deeds were still possible and the power of kindness, friendship, and love were able to overcome evil. When considering Tolkien’s context and personal life, these desires to return to earlier times should not be interpreted as some anti-progressive screed, but instead reflect Tolkien’s desire to return to his life before his experience in world war one. The hope to return to the ancient battles of Beowulf or other myths should be understood as contrasts to the modern charnel house that greeted him in the trenches of France, not as a power fantasy of some sword wielding alpha male.

See, Tolkien never, not even with the Return of Aragorn to the throne in Minas Tirith, allows that ancient glory alluded to in those names to be recaptured. The greatest example of this is the Eldar. The elves who stayed to fight the War of the Ring do not remain to make Middle Earth Great again, restoring the old kingdoms of the Sons of Feanor. No, they depart, over the sea, to the far green country never to be seen again. With them, they take magic, and beauty, and peace, making Middle Earth much less wondrous. The connection between the leaving of the Eldar and the end of the wonder of youth that we all feel as we grow old, gather scars, and meet the world as it is, not just how it could be, is the power of Tolkien, not the ideological project that Thiel and Yarvin embrace. If you don’t believe me, just ask Tolkien himself who famously said that he “disliked allegory in all its manifestations.”

Towards the end of The Return of the King, after the Shire has been saved and the evil of Sauron defeated. Galadriel, one of the oldest of the Eldar ever to walk Middle-Earth begins her voyage to the undying lands. She stops in the Shire, and engages in all manner of Hobbit-like revelry, dancing and drinking with the rest of the Shire-folk. Galadriel also brings with her a few seeds of the Mallorn tree from Lothlorien to plant in the Shire before she leaves forever, never to return. Her gift is not wasted, and Samwise plants the seeds which grow into the last Mallorn Tree that ever stands in Middle-Earth. Even when Lothlorian fades, and magic leaves Middle-Earth, the Mallorn tree still stands as just a piece of what was lost.

I always found this episode at the end of the story moving. The Mallorn Tree seemed to reach outside the pages of “The Lord of the Rings” and be a small piece of the story I could take with me out of Middle-Earth and into the “real world.” I wonder if Tolkien was able to preserve his Mallorn Tree through the trenches of the Great War, so that even when he was surrounded by suffering and death he could still remember a better time, or a better place.

And it’s not like Lothlorien was perfect, or that the days during the War of the Ring were peaceful, or that the Eldar that lived within the trees were pure. One of the other inconvenient facts of Tolkien’s wistful and melancholic view towards the past fascists hate to grapple with, is that every one of those ancient and great nations of Middle-Earth were riddled with corruption, evil, and hatred. Whether the kin slaying done by the Sons of Feanor, the tyranny of Az-Pharazon as he listened to Sauron’s council and made war against the Valar, or the greed of the Dwarves as they dug in Moria, no great nation that inspires songs and tales was an uncomplicated force for good much less perfect. But when they are remembered in bleaker times, the realities of their greed and ambition fall away, and when the name Numenor is whispered on the streets of Minas Tirith the parts that were are what is remembered.

When young hobbits look at the Mallorn tree, they do not think of the War of the Ring or the hatred between the Elves and the Dwarves, instead they think of the beauty that was once in the world that has passed away. The Mallorn tree stands to show that Lothlorian was once a place, and at least some parts of it were beautiful.

As I watch masked men of the American secret police roam the streets, I cannot help but think of the Mallorn tree and feel wistful for better times. I know my melancholy is not universal, those who were ground under the heel of Numenor surely do not see beauty in its edifices, but I also do not feel like I am alone. Perhaps I am a fool for ever believing that in the words of Martin Luther King Jr. we could “transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.” Or the words of Abraham Lincoln when he said “that government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish from this earth.” I mourn that living up to those words seems less and less likely every passing day, even if they always were an illusion.

I think of the Mallorn tree in the Shire, and hope to plant my own. Not to hold up the past as an uncomplicated better time or to ignore the evil, hatred, and corruption that have plagued America from the beginning, but instead in these evil times to just remember that America was once a place, and at least some parts of it were beautiful.